Back around July of 2004, I was in the beginning of the time I consider my "exile" period in my first post-graduation job as sports editor of the Bogalusa (La.) Daily News. I would spend two years there, which were pretty eventful, both personally and for the rest of the state (duh). I got to know a handful of high school coaches pretty well, and one sit-down with then-Bogalusa High head coach Buddy Fornet has always stuck with me. I was interviewing him as a part of the big start-of-the-season football preview we put out every August, and I asked the veteran coach how the game had changed in his decades on various sidelines. Keep in mind, this was right we began to see the different versions of the spread offense really become mainstream in college football with coaches like Mike Leach, Urban Meyer and Rich Rodriguez. "Not as much as you think. Football's still ‘bout blockin' and tacklin'. You move the pieces around a lil bit differently, but checkers is still checkers."

Whether it's been breaking down LSU's own offensive struggles or Oregon's offense, one thing I've tried to make clear is that the secret to really good college offenses isn't complexity, but simplicity. And it's not hard to see why. College football still isn't professional football (insert Auburn/Ohio State/Miami joke here). Coaches have just 20 dedicated hours to work hands-on with their players each week (yes, I know the players spend a lot more actual time than that working on football, but we're talking direct coaching), that has to fit around players' class schedules to boot. In the NFL, a coach can throw a phonebook full of formations, shifts, personnel groupings, adjustments, protections and audibles at his team and STILL continue to adjust it week-to-week as the season progresses. Why? Because professional football players don't go to class. Playing football is their full-time job, and they can spend as many hours they want in any given day or week working to become as good at it as they possibly can. And if they don't, their team will find players that will.

In college, the smart coaches focus on executing a core group of plays, and then building off of that as the season allows. And that brings us to the third offensive dynamo LSU will see this month, West Virginia Head Coach Dana Holgorsen.

He is, as most of us probably know at this point, the former coordinator of brilliant offenses at Oklahoma State and Houston, and former assistant under Mike Leach at Texas Tech. The 40-year-old former receiver under Leach and then-head coach Hal Mumme at Iowa Wesleyan has led offenses that have averaged 41 points and 543 yards per game since 2007. Holgorsen has taken the Air-Raid offensive principles of Leach and Mumme and possibly perfected the attack by adding an increased emphasis on the running game and play-action.

The Mumme coaching tree has expanded to include names like Leach, Holgorsen, Mark Mangino, Kevin Wilson, Kevin Sumlin, Sonny Dykes, Seth Littrell, Robert Anae and Lincoln Riley to name a few, and his Air Raid offensive principles are now seen at every level of football, from high school to the passing games of NFL teams, including the New Orleans Saints, Indianapolis Colts, New England Patriots, Green Bay Packers and Philadelphia Eagles. We know the Air-Raid as a heavily pass-first system built out of the shotgun formation and noted for a wide-split offensive line, designed to create longer pass-rush lanes for defensive linemen. The wide splits do create shorter blitz lanes for linebackers and defensive backs, but the attack's audible system is designed to exploit those blitzes with quick passes.

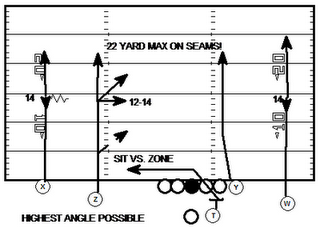

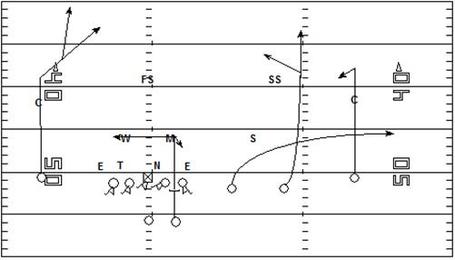

Leach took the attack to another level at Texas Tech, mostly due to his love for down-the-field passing and his favorite passing concept, Four Verticals:

It's a concept we've discussed before, and as you can see it's quite the literal name. Four receivers run vertical routes down the seams of the defense. The Idea being, that regardless of the coverage one of the four receivers will find enough space to make a play. And of course the receivers have latitude to adjust their routes to find that open space, whether it's cutting the route off into a crossing pattern, going to the post, etc...In the video below you can see the Saints running a version in which Jeremy Shockey crosses the field to the opposite hash before continuing his route down the field.

It's a simple idea that a college offense can perfect in practice and be easily adjusted on the fly as the defense adjusts to it. That simplicity was a big reason why Leach's Texas Tech offense thrived year in and year out as personnel change. There's only about 12-15 plays in the book, each player in the offense learns one specific position that doesn't change. As West Virginia receivers coach Shannon Dawson explained last spring, players like Wes Welker, Michael Crabtree and Justin Blackmon were so ridiculously productive in this offense because they only learned the handful of routes that their particular receiver position ran in the playbook, and could focus on perfecting them. If you're an inside receiver on the right side, that's the position you will always line up in. It even allows a team to practice faster, because the players are almost always lining up at the same spot on the field.

It should be noted that this is one of NFL scouts' biggest complaints about the attack -- that it doesn't teach players to master all facets of the position -- but it's pretty tough to argue with the results. In fact, this approach has been something of a staple to the Indianapolis Colts in their last decade with Peyton Manning. Their receivers almost always line up on the same sides of the formation. There's movement and motion, but Reggie Wayne has always lined up on Peyton Manning's left hand side, and Marvin Harrison was always to his right. Talent, and execution, will always triumph over scheme.

Holgorsen took Leach's ideas with him to the University of Houston under another Air-Raid disciple, Kevin Sumlin. There, he further streamlined the playbook to about 12 plays, while increasing the emphasis on motion, misdirection and the running game. The results were immediate. Seven thousand yards of offense (5,000 passing/2,000 rushing) in year one. In year two, five receivers had more than 500 yards, including three over the 1,000-yard mark. Below are some cutups of the Case Keenum-led attack that are sure to make Sad Greenie sad again.

The first difference you'll notice is that Holgorsen is much more willing to put his quarterback under center. There's also a lot of the more basic run plays we're all used to seeing -- the inside zone, stretch, trap and counter -- along with play-action. The passing game will also set up some misdirection passes based on the screen look (bubble and tunnel screens are of course mainstays of the Air-Raid).

As you can see in the above video, a single receiver will sometimes hang back to fake a screen even as the rest of the wideouts run downfield. This can help to not only fake out the defense by maybe drawing their eyes to the line of scrimmage, but to also provide for another outlet receiver.

As mentioned before, the playbook was cut down to about 12 pass concepts, which Holgorsen says he can install in three days of training camp. He eschews the horizontal stretches that Leach and other Air-Raid guys favor, most notably "Mesh," and focuses on the more vertical ones like:

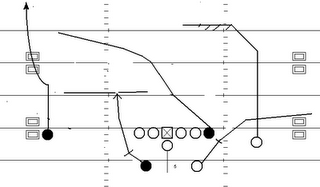

Y-Cross

Look for West Virginia to use this concept off of play-action, hoping to suck the linebackers up the field and create space for the Y-receiver.

Y-Stick and Y-Corner

via bruceeien.com

Here's another video of the Saints running the Y-Stick concept:

The Shallow Cross (seen here in assorted variations)

via bruceeien.com

Bobby Petrino's offense makes a heavy use of this concept as well.

And Houston, which is another concept that can be used off of play-action.

The offense continued to evolve last season when Holgorsen joined Mike Gundy's staff at Boone Pickens University Oklahoma State. There, the offense shifted more towards stud running back Kendall Hunter, and more multi-back sets, including some full, nine-route pro-style passing trees. I would imagine this was Holgorsen gelling with his head coach, known as a solid offensive mind in his own right. But Holgorsen's love of incorporating the running game does come by naturally, per some quotes from this interview with Andy Staples:

Leach: "Who was open?"

Holgorsen: "Mike, I know you don't want to hear this, but there wasn't anybody open."

Leach: "What do you mean there wasn't anybody open?"

Holgorsen: "They dropped nine people and they double-covered all our guys. There was nobody open."

Leach: "Well, how'd they get pressure on the quarterback?"

Holgorsen: "Well, because one guy can't block one guy for seven seconds."

Between games, Holgorsen would entreat Leach to call a few more running plays to keep the defense honest. Leach - who, to be fair, won an awful lot of games doing it his way - usually declined and kept right on calling passes....

In Stillwater, Holgorsen borrowed from other spread running gurus like Chip Kelly by developing something of an inverted wishbone set known as the diamond formation.

via lh5.ggpht.com

This new version of the three-back set, incorporated into a pistol look, is popping up on more and more teams, including Oklahoma and TCU. Here's an outstanding link on the Cowboys' use of it via Offensive Breakdown. Why use it? For the same reason the original wishbone was once the most popular formation in the college game -- it gives the offense a balanced look with an equal chance of running power or misdirection plays. With three backs, it's easy to get a defense biting on motion in one direction while the ball heads in another. That also goes for the passing game, where it's also easy to cross up linebackers and safeties with as the bunch splits up. It will also very often result in one-on-one opportunities for the receivers, something Justin Blackmon exploited with big-time results in 2010. Again, Holgorsen loves play-action passes -- they're just another way to push the ball down the field. Some teams have used it for a triple-option look, though certainly not OSU in 2010. And Geno Smith has just nine rushing attempts in three games, for a net of -3 yards, so don't look for him to run much (although he is athletic enough to make plays with his feet on occasion).

Thus far in Morgantown, the passing game has been far more successful than the run, but that hasn't stopped the Mountaineers from striving for general balance. The split on first-down playcalling is pretty even through the first three games, 50 passes to 46 runs on first down, although the passes have been far more successful (68-percent completions for 350 yards compared to 119 yards rushing). Ditto redzone playcalling, with 26 runs to 24 passes. Overall, it feels like Holgorsen is still trying to get a feel for what this team does well. Though he certainly has a solid quarterback on hand in Smith, who completed 65 percent of his passes last season with 24 touchdowns and 7 interceptions, and a near-70 percent this season with 7 TDs and one pick.

As for how LSU will go about defending this attack, I'll have some more on that later in the week, with some help from a special guest star.