You didn’t start a business so that you could learn accounting, but learn you must! Here’s a little help.

QuickBooks lets you switch between two radically different methods of accounting with a click of a button. It’s nice to have accommodating software, but which one should you pick?

Never heard of either of these? Time to learn:

“Cash-Basis” accounting means you only count revenue and expenses that you actually have. Things that count: Receiving a check or credit card payment, writing a check to the telephone company, paying your credit card bill. Things that don’t count: Receiving a purchase order, receiving the bill from the telephone company, charging something on a credit card. So it counts only if real, hard cash comes in or goes out. Stuff that hits a bank account.

“Accural-Basis” accounting means you count pledged revenue and expenses. It’s the opposite of cash-basis — what counts are purchase orders (customers pledging to pay you), bills arriving (vendors you’re pledging to pay), and credit card purchases (debt you’re incurring). It doesn’t matter when you pay the bill or when the customer actually sends you a check.

So which should you use?

Which is better for paying taxes?

The IRS allows you to pay taxes with either style of accounting, but you want to use cash-basis.

You have to pay taxes with cash. With cash-basis accounting, you show a profit only if you have excess cash actually in your possession. If it’s in the bank, you can set it aside for taxes. It’s like a dagger through the heart, but you can afford it.

Not so with accrual-basis. If you get a huge purchase order from a new customer, that would show as income; then the IRS wants their 30%, but since the customer hasn’t paid (and you, silly silly, paid your bills on time), you don’t have the cash to pay. Oops!

Cash is king, much of the time.

You’ve probably heard “cash is king:” Real cash (not purchase orders) pays your mortgage, keeps the internet up, and pays employees. Bills can be paid late, but they don’t take “accounts receivable” at the grocery store.

Thus for daily operations, cash-basis wins again. When you’re deciding whether you can afford a new advertisement, whether your payroll check is going to bounce, or whether you can actually take some cash out for yourself this quarter, you have to use cash-basis.

Which is better for understanding how the business is doing?

So far cash-basis has won every time, but when you shift your attention from daily operations to business analysis, cash is not king.

Here are questions best answered using accrual-basis accounting:

- Am I taking in more money than I spend? (How close? How is it changing?)

- Am I staying inside my own budget?

- Which expenses are eating my lunch?

- Are there unexpected expenses?

- How do I build a budget for the next six months?

Let’s take the first question as an example. Revenue-versus-expenses is important for every business at every stage of its life; no duh. What you’re really comparing is “revenue won” versus “expenses incurred.”

The trouble with cash-basis accounting is that it has nothing to do with when you incurred the expense, but rather when you paid the bill. You might have paid late (on purpose or otherwise). You might have paid early for a discount. The bill might have appeared on weird days so it just so happens that you paid a monthly bill twice in March and skipped April. Same with revenue — at Smart Bear it was common for a purchase order to be paid 5, 30, or even 90 days late. We won the order — the marketing worked, the sale was approved, tech support satisfied the end users — but who knows what in month the revenue would actually hit the bank account.

With the bulleted questions above, these cash-basis variances hide the important story. You need to measure intent, not the chaotic reality of money moving around.

Jason’s Scaredy-Cat Method:

Cash-basis revenue + Accrual-basis expenses

I’m conservative and pessimistic by nature. Yeah, I know, not adjectives you’d normally associate with someone who starts companies instead of holding down a job, but that’s not news. And since I don’t have an online accounting degree, I need something simple.

So at Smart Bear I combined the worst of both worlds to build a safe model of how much money I could afford to lose on experiments. Why this peculiar cash/accrual split?

- Revenue only counts when the cash is in the bank (cash-basis). I’m uncomfortable incurring expenses when I don’t know when or whether a customer will pay. Collections are uncertain; I won’t depend on a dollar until they can’t take it away from me.

- Expenses count immediately (accural-basis). I’ve incurred the cost, so for planning purposes I have to pretend that cash is gone. Sure some cash-revenue might appear before the bill is paid, but it might go the other way, causing a temporary cash-poor condition.

This isn’t always an appropriate method. It’s bad for budgeting or forecasting because you’ll underestimate what you can afford, so for example you’ll unnecessarily limit marketing efforts. It’s bad when you’re getting your arms around the “revenue versus expenses” example because you’re not comparing the same kinds of money.

But this method is perfect when pondering an experiment. It’s perfect when you’re wondering if you can afford $5000 in graphic design work, a new $6500 marketing campaign, or whether you can hire someone and have 3 months of runway to discover that was a massive mistake.

It’s right for experiments because with this method you know for certain that even if the new effort is a colossal failure, you really can afford to lose that money.

More advice, more methods

What other methods or advice do you have for the intrepid entrepreneur who just realized she has to know something about accounting? Leave a comment and join the conversation.

35 responses to “Accounting for Startups: Cash-basis or Accrual-basis?”

Always thought that “Accural-Basis” was a better option if you had a nice cushion in your bank account. Personally prefer the cash basis.

.-= Sergey’s latest blog post: ERIC =-.

Speaking as a past accountant and financial statement auditor – GREAT POST JASON!

I’ve run a few small businesses and although the cash-basis is helpful for the sake of simplicity, I find that I always end up going the accrual route. The information it provides is just too vital to not use it.

For me, I look at what cash is available, and make a budget based on that. I do not budget based on the accounts receivable (money I have yet to receive that I’ve earned). I’ve been in a few situations where the client just ends up not paying, or they run away after you deliver (hopefully you had them pay 50% before starting the project).

So my advice? Budget based on actual money. You can do it, but it takes some self control.

Great post, thanks for sharing.

.-= Chris Mower’s latest blog post: Entrepreneur Interview: Chris McClain of Chris McClain Productions =-.

Of course one of the points is that you don’t pick just one, but rather use whichever one is most useful for specific tasks.

“you show a profit only if you have excess cash actually in your possession. If it’s in the bank, you can set it aside for taxes. It’s like a dagger through the heart, but you can afford it.”

Unless you’ve spent it… ooops!

Perhaps I’m a coward, but I pay a man who knows much more about accounting than I do. My current business activities are well defined, and payments are regular and roughly the same size. I keep a business current account and a business ‘saving’ account. I move the VAT from each in-bound payment into the ‘saving’ account until time to pay to HMRC. I also move 1/3 or thereabouts from all in-bound payment to cover tax, broadly speaking. Day-to-day stuff remains in the current account, and I try to route all business purchases through a business corporate card, as much as to minimise my own personal cashflow. That’s because, as a boot-strapper, I try to minimise my ‘committed’ costs, such as salary, to retain good working capital in the business. When I feel there’s more than enough of a ‘cushion’, I redistribute the remainder as dividend to shareholders (i.e. me).

The thing that works for me, at the root of all of this, is to ensure that I build and protect that ‘cushion’, striving for a sensible amount that’s a bit like mummy bear’s porage – neither too ‘hot’ nor too ‘cold’ – just right. The size of that amount will depend on the type of business, but in my case it’s three months’ full expenses, plus all taxes and financial liabilities outstanding.

Boring, but with some things you need to be Mr Sensible Shoes…

In Canada, home of the invention of pork projects and tax-free perks for politicians, we have to use accrual basis by law.

Amen, Jason! At last someone started speaking about business management!

I live in a country where the average entrepreneur has no interest in the economic and financial equilibriums nor has the cultural background to understand it. That’s one of the reasons my country is losing traction. Companies are culturally unprepared to go abroad or to grow beyond small sizes.

I’m fighting my small war with a series of posts starting here http://www.straysoft.com/dblog/articolo.asp?id=67 in the nearby field of business intelligence consulting.

Keep working on this, as you are popular enough to take the issue to mainstream attention.

.-= Stray__Cat’s latest blog post: Why you should get an MBA =-.

great info – but does standard software support hybrid accounting? i.e. mixing cash and accural the way you suggested?

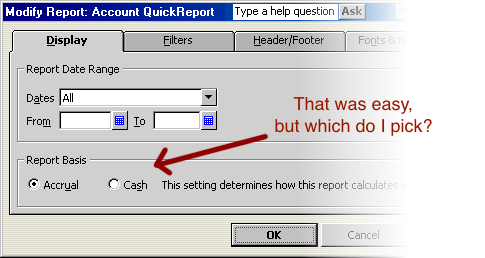

When you “account” for events like sending a bill or receiving payment or a bank statement, those are entered in any system. The question is how you build the Profit & Loss report.

Generally accounting systems will let you change the nature of that report as cash-basis or accrual-basis easily.

So you’re not “picking” a way until you report on what’s been accounted for.

Thank you very much. I’m just getting to grips with my accounts. Got first years end of year return to do soon, scared as don’t want to annoy the tax man. I think I will probably go and see an accountant and concentrate on the side of the business I know.

Good luck with your accounts.

Absolutely true. The cash basis precludes a lot of wishful thinking and pointless fantasies as well.

.-= Steve French’s latest blog post: The Kill Shot and Project Management =-.

Good post, and I think you hit the nail on the head – accrual gives you a better picture looking forward (still very short term) and cash basis gives you a better backward looking picture (imho). And I actually think the scaredy-cat method is very appropriate for services firms – after all, the expenses you accrue you will have to pay – regardless of whether you collect on your receivables, in most cases. So it is a good way to make sure you don’t get into a bind.

.-= Scott Francis’s latest blog post: Testing and Performance – #bpmCamp 2010 @ Stanford =-.

When, oh when are you going to turn the gems in your blog into a book?! Please do the world a favor!

this is combined approach is how you are obliged to account under german law. it is argued with the bigger emphasis on the security for creditors. But in the end a realistic view on the company (what’s in the pocket and what has still to go) is easier to grasp for getting an overview.

Great share. I personally advise all of my clients to go the accrual basis even if they don’t “have to” yet. 1. for scalability in the future and 2. it just paints a better picture of how the business is doing. I then of course teach them to use the Statement of Cashflow and multitude of other metrics to determine how they are doing on their “Cash.”

.-= Michael Hsu’s latest blog post: Newest Member to the DeepSky Family! =-.

Great info, thanks for posting. I like your scaredy cat method, and will definitely start using it when appropriate. Although internally you can use both cash and accrual, you’re only allowed to use one for the IRS. I read that if you use cash-basis, you’re not allowed to claim bad debts because technically you never earned the money. Is there any way around that?

.-= Zuly Gonzalez’s latest blog post: Spammers Create Fake User Profiles on Facebook =-.

So a “bad debt” typically means someone promised to pay (i.e. PO) and you issued an invoice (that’s the “debt” owed you) and they didn’t pay. So correct, in cash-basis that cash never appeared.

But the only reason you need to write down bad debt is because in accrual-basis that revenue was counted as income, and you need to undo that. In cash-basis there’s nothing to undo.

In short, either way your bad debts aren’t counted, so that’s not really a consideration.

Sorry, I don’t think I phrased my question clearly. I believe the IRS allows you to deduct a bad debt as a business expense (although I’m not 100% sure on that). So for example, if you sell someone 100 widgets, but you only receive payment for 40 of them, you can claim the cost of the remaining 60 widgets as a business expense. If that’s the case, will the IRS allow you to deduct the bad debt even if you use cash-basis accounting?

.-= Zuly Gonzalez’s latest blog post: Spammers Create Fake Facebook Profiles =-.

For some reason Cash-basis revenue + Accrual-basis reminded me of that SNL skit from the beginning of the financial crisis:

Don’t Buy Stuff You Can’t Afford

Great post and good advice, I like the scaredy-cat method and will immediately add it to our monthly reports! One little point (in the US at least, for tax purposes) credit card purchases made on a company card issued by a bank are treated as cash purchases on the date charged.

I have found that the best way to avoid paying tax as a small business owner is by not making any money – this way you win and the evil government loses.

.-= Jorgen Sundberg’s latest blog post: Great Britain, Great Personal Brands from Yesteryear =-.

Simple answer, accrual basis for management & accounting purposes; cash basis all the way for tax purposes (if you qualify).

Good post Jason;

In Accrual basis you indicated including “purchase orders (customers pledging to pay you)” – actually a purchase order from the customer is a contract for future supply. Therefore it’s only when goods have been delivered or services rendered (invoiced) that you have to “account” for such as revenue.

@John Clark follows the best idea that a small or new business should undertake – put aside 25-30% to cover future tax liabilities.

The best way to account, as Michael Hsu, alludes – is to

1) Adopt Accrual basis so that you can snapshot your business at any stage (past for performance / future for budgeting, forecasting and growth)

2) Understand and use cashflow forecasts – cashflows allow for timing differences, e.g. the quarterly rent bill due in advance, the 30-60-90 days customers typically take to settle bills, 30-60 days to settle vendor bills, 3 months say to settle VAT bills, 18 months to settle corporation tax.

And 3) use cash basis for Tax if you qualify (as alluded Tommy Jaye)

And finally – There’s really no substitute for good advice – get an Accountant/Auditor on board, typical small businesses and start ups will only need them once a year or so.

You’ve done it once again. Amazing read.